Gateways to Wonderland

Cinnabar, Mont. & The Northern Pacific RR

Copyright 2020 by Robert V. Goss. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by an information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the author.

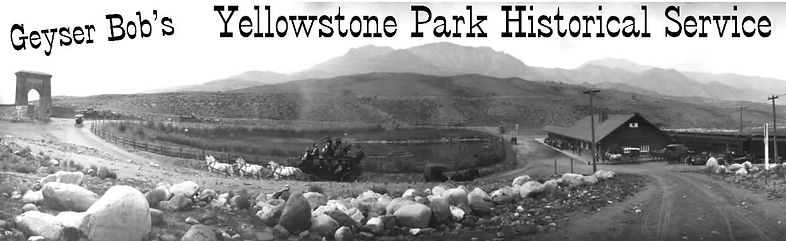

Valley of Cinnabar, ca1883. A Boudoir-Series Cabinet Card by photographer Carleton Watkins.

The Early Days . . . .

The small community of Cinnabar was located three or four miles north of Gardiner and was the temporary end-of-line station of the first railroad service to Yellowstone National Park. It was the primary gateway to the park from 1883 to 1903. The town’s name derived from nearby Cinnabar Mountain, named during the mid-1860s by miners who originally thought the ‘red streak’ on the mountain was the mercury ore cinnabar. In August 1870, the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition observed the formation and named it The Devil's Slide.

. A traveler in 1874 noted that Cinnabar Mountain was, “prominent for its height and isolation from it compeers, and significant from the fact that the Devil took a slide down its Eastern slope when he was apparently red-hot, leaving in his wake a well-defined trail that can be seen for fifty miles, having the appearance of fire-clay.” [Bozeman Avant Courier, 4Sep 1874]

Devil's Slide, photographed by Wm. Henry Jackson in 1871.

The Bozeman Weekly Chronicle published a Song of Cinnabar Waters on April 18, 1883, based on an unfortunate drunken row, when David Kennedy shot his boon companion James Armstrong. The "Vanderbilt" was a silver watch willed to “Davie” in the event of James’ death. It may have been penned by William Davis, who was deemed "The Poet Laureate of Yellowstone." A portion of the song follows:

CINNABAR.

Long, long ago, one could easily see,

Yellowstone Valley had been on a spree:

The mountains were raised, the canyons were

sunk,

And old Mother Earth got terribly drunk.

The devil got as drunk as a devil could be

And slid to the bottom of Cln-na-bar-ee!

Fill up your demijohn, fill up your can,

A health to the devil, damnation to man !

Give Davie my Vanderbllt, let him go free,

To slide when he pleases down Cln-na-bar-ee!

Not long ago, It was Sunday, and we

Sent three of our boys down for Cln-na-bar-ee

Mad-day Is moon’s-day, each emptied his cup,

Reason ran down, and our passions ran up.

Bullets were flying, and two entered me,

Perhaps I am dying, from Cln-na-bar-ee.

Beginnings of Cinnabar City . . .

Abel Bart Henderson, who began prospecting around Yellowstone in 1867, started building a road in 1871 from Bottler’s Ranch near Emigrant to Mammoth Hot Springs. He acquired land around Stevens Creek and he and his brothers established a ranch in 1877. Clarence Stevens, George Huston, and Joe Keeney all owned parts of the land at various times. Huston and Keeney purchased part of the Henderson Ranch at Stephens Creek Nov. 19, 1883, which totaled 116.45 acres. Apparently Keeney retained some land for himself and built a ranch, and they resold the rest later that year to Carroll T. Hobart, a Northern Pacific RR Superintendent and manager of the Yellowstone Park Improvement Co. A plat map was created and the site became the town of Cinnabar. Construction on the Northern Pacific's Park Branch Line began in April of 1883 from Livingston to Cinnabar and was open for business on September 1 of that year and in 1884 began in earnest transporting tourists to enjoy the breathtaking beauties of Wonderland. The Cinnabar Town Site Co. was later incorporated in 1895 by J.D. Finn, H.J. Hoppe, and A.J. Campbell.

Reportedly, Hugo Hoppe and family moved into the Cinnabar area ca1883, where Hugo created his freighting company to haul goods from the new railhead in Cinnabar to and from the mines at Cooke City, Montana. He also engaged in other enterprises over the years. During 1884-1885 Hugo managed the new National Hotel at Mammoth Hot Springs. He managed the Cinnabar Hotel from Jan.-Jun. of the following year. More of that later.

Cinnabar Townsite in 1884. The town is still quite desolate at this point. The building behind the rail car at left may have been the Wakefield-Hoffman stables. The first year or so, the NPRR used two sleeping cars and a dining car for travelers until other accommodations were available.

[F. Jay Haynes photo, Montana Historical Society]

Undated photo of the H.J. Hoppe Ranch, just south of Cinnabar. The view is toward the Yellowstone River.

[Billings Gazette, 7Sep1958]

The Northern Pacific RR Moves in . . . .

A land dispute regarding Buckskin Jim Cutler's mining claims between Cinnabar and Gardiner prevented the railroad from extending the line to Gardiner, the desired destination. A small town quickly grew up around the Cinnabar depot and provided basic visitor services. The post office opened in 1882, in anticipation of the railroad's arrival and a small depot was soon built to accommodate travelers to the park. The Butte Miner announced on Aug. 29, 1883 that, "The Yellowstone National Park branch of the Northern Pacific railroad is now completed to Cinnabar, 51 miles south of Livingston, and will be open for business on Sept. 1st, after which time parties can go directly to the park without staging."

GARDINER DEFEATS

CINNABAR FOR THe YELLOWSTONE LINE

Gardiner, located within a few Inches of the line of the Yellowstone park, is to have a railroad within a few weeks, the Northern Pacific having decided to extend Its park branch from Cinnabar to that town at once. These two towns are only four miles apart, but ever since the park branch was built, the Cinnabars have had the best of It. There are only 250 of them when they are all at home, which is not often, but notwithstanding the small number they have been up and doing. Think of a town of 250 persons having its own electric lighting plant and water works!

Gardiner has both, and in their possession the place bears the distinction of being the only one of its size in the United States that can afford such high class luxury. Heretofore Cinnibar [sic] has been the jumping-off place for Yellowstone park tourists, but hereafter it will take off its hat and with bland smile and a low courtesy exclaim, “After you, my dear Gardiner!

[Butte Daily Post, 13 May1902]

Beginnings of the Stagecoach Era . . .

George W. Wakefield and Charles W. Hoffman of Bozeman established the Wakefield & Hoffman stage line early in 1883 and provided service from Cinnabar to Mammoth and into the park under an exclusive agreement with Yellowstone Park Association (YPA). The Helena Independent Record announced on July 2, 1884, that, “this week, the coaches, jerkies, and single and double "buckboards, numbering about forty vehicles in all, belonging to Wakefield & Hoffman, were moved from Bozeman to Cinnabar and Mammoth Hot Springs, to be in readiness for the accommodation of park tourists.” They had previously operated from Livingston to Cinnabar until NPRR’s line was open to Cinnabar.

Top Right: Wakefield & Hoffman's Stage Line ad.

25Jan1884, Livingston Daily Enterprise.

Bottom Right: Geo. W. Wakefield's Bozeman and National Park Stage Line letterhead from Dec. 16, 1883.

Top: Northern Pacific RR train at the station in Cinnabar, 1894. The locomotive in number 418.

[F.J. Haynes photo, Montana Historical Society]

Bottom: Passengers alighting from train and loading on coaches for a trip to Wonderland, ca1896. The Depot is in the background.

[Burton Holmes Travelogues, 1905 version]

Top: Passengers unloading from a Northern Pacific RR car Cinnabar, ca1896.

[Burton Holmes Travelogues, 1905 version]

Bottom: Train passengers loading on coaches for a trip to Yellowstone, ca1896. The building on far left appears to be Wakefield & Ennis office, who conducted camping excursions into Yellowstone 1896-1897. White bldg on far right is the W.A. Hall Store, with the Cinnabar Store to its left.

[Burton Holmes Travelogues, 1905 version]

Beginning in the 1884 Yellowstone summer season (June to mid-Sept), trains ran daily from Livingston to Cinnabar, in both directions transporting tourists in and out of Yellowstone. (During the off-season trains ran one to three days a week, depending on demand) Wakefield bought out Hoffman at the end of 1885, and was the primary stage operator until he was squeezed out late in 1891. Most visitors utilized the services of the authorized transportation carrier of the Yellowstone National Park Improvement Co. (Yellowstone Park Association in 1886 and Yellowstone Park Transportation Co in 1892). With these companies passengers would ride in Tally-Ho stagecoaches led by a team of six horses from Cinnabar to the National Hotel at Mammoth Hot Springs. From there smaller 4-horse, 8-10 passenger Abbot Downing Concord coaches would carry the guests around the park, staying at different hotels for 5-6 nights before returning to Cinnabar and the train to Livingston.

Other transportation/camping companies for the traveling public were also available, including, A.W. Chadbourn in 1884, the Wylie Camping Co. by the 1890s, a number of smaller private coach companies and by the late 1890s, the Shaw & Powell Camping Co. Wylie and Shaw & Powell utilized portable tent camps with all the comforts possible, and were located at all the major points of interest, with Lunch Stations along the route. Some tourists opted to hire their own carriage and these “sage brushers” traveled the park on their own accord. These companies all operated out of Cinnabar until 1903.

W.W. Wylie Camping Co. Cinnabar ad in the Helena Independent Record, 14Aug1896

A.W. Chadbourn information from the Livingston Enterprise Souvenir, 1Jan1900

Shaw & Powell Camping Co. information from the Livingston Enterprise Souvenir, 1Jan1900

With the formation of the Yellowstone Park Transportation Co (YPTCo) in 1892, and their pressure to create transportation monopoly in Yellowstone, Chadbourn and many of the other small, private transportation operators were kicked out of the park after the 1893 season, however Wylie managed to continue his operation and Chadbourn and a few others managed to regain their privileges. Freight operations also developed to service the hotels in the park, the Army at Ft. Yellowstone, and the mines at Jardine, Cooke City, and Horr. Hugo and W.M. Hoppe were operating the Cinnabar & Cooke Transportation Co. at least by 1886, hauling freight from the railhead at Cinnabar to the mines in Cooke City and stops in between. They also hauled freight for YPA.

National Park Hack & Express Line

Frank M. Hobbs and Lawrence Link

Livingston Enterprise, 9Sep1884

Cinnabar and Cooke Transportation

W.M. Hoppe

Livingston Enterprise, 4Dec1886

Cooke Transportation Line

A.T. French

Livingston Enterprise, 30Nov1889

Geo. Eastman of Rochester, New York, together with his mother, Mr. and Mrs. Walter Scott Hubbell and Dr. E.W.. Mulligan and wife passed through town [Yakima WA] on the west bound overland Saturday morning, The party has been on the road for the past three weeks stopping at all points of interest, but remaining most of the time in Yellowstone Park. Their itinerary for the next three weeks will be via Portland, Vancouver, Bampf Springs [Banff] and St. Paul thence back to Rochester. Eastman has a national reputation derived from the great kodak which he perfected and Walter Scott Hubbell is considered one of the greatest lawyers in Western New York.

[Yakima Herald, WA, 22Jul1902]

Mr. George Eastman of Kodak fame is now touring the west accompanied by a party of friends. The party is traveling on the private Pullman car Pilgrim. Mr. Eastman was to have come west over the C.P.R. [Canadian Pacific RR], but owing to the recent suspension of traffic he came west from Rochester, New York, over the Northern Pacific. He returns East over the C.P.R., making stops at Banff, Field [Yoho Nat'l Park] and the various other mountain resorts ls on the line of the railway in this province.

[The Province, Vancouver, 15Jul1902]

Coaches on road between Cinnabar and Gardiner, July 1902. One of the few known images of stages on that section of road.

[Courtesy Eastman Museum, 2006.0126.0072]

Coaches on road between Cinnabar and Gardiner, July 1902. The carriage at left appears to be from one of the various camping companies.

[Courtesy Eastman Museum, 2006.0126.0069 & 0070]

Northern Pacific Pullman Cars at Cinnabar, July 1902. The building at right may have been a freight depot at the east end of town.

[Courtesy Eastman Museum, 2006.0126.0069]

Left: George Eastman and Walter Walter Hubbell along the road from Cinnabar to Gardiner. Hubbell was a close friend and vice-president of the Eastman Kodak Co. [Courtesy Eastman Museum, 2006.0126.0065]

Right: Maria Eastman, George Eastman's mother, and her nurse aboard Coach 38, Yellowstone Park Transportation Co., at an undisclosed location in Yellowstone. [Courtesy Eastman Photographic Collection Y119]

A Lady's Trip to the Yellowstone Park

By O.S.T. Drake

A Brief Description of the Cinnabar Hotel in 1887

". . . Livingstone, on the Northern Pacific Line, is the station whence we took our departure for the National Park, by a short line 57 miles in length, which deposited us at Cinnabar, ten miles from the Mammoth Springs . . . Cinnabar, where the line terminated, consisted of a wayside saloon and a few huts. From here we drove to the Mammoth Springs"

"That night [after leaving Canyon on their return] we slept in tents at Norris' Camp, breakfasted early and departed, reaching the Mammoth Springs again at noon ; then on to Cinnabar; the scenery very lovely. High on a sharp rock above the Yellowstone river we spied the eyrie of an eagle, which resembled a mass of sticks on the edge of a perfectly inaccessible rock. There sat the eagle, showing her white throat, sunning herself in her majestic solitude. The hotel at Cinnabar turned out to be a little timber house, consisting of a bar and back parlour, and two or three bed-rooms above. A married couple kept the house ; the wife said she had never had a lady under her roof before. They gave me a very clean bed-room, provided with the only jug and basin in the house. There was no door, but she nailed a sheet over the door-way and unnailed it in the morning ; the food was excellent, and the good woman waxed quite pathetic in her regrets over the fact that we were hardly likely again to meet in this world. Next morning we took the train at Livingstone, and pursued our journey to New York."

From: "Every Girl’s Annual" 1887. Edited by Alicia A. Leith

Reminisce from Al H. Wilkins, Yellowstone stage driver, as told to Grace Stone Coates

Great Falls Tribune, 23 Feb 1933.

IN 1885-86 the little town of Cinnabar was a lively place. It was the terminus of the Yellowstone park branch of the Northern Pacific railroad, where tourists transferred to horse-drawn coaches. Just across a little divide four miles away the town of Gardiner was coming into being. At Cinnabar the late Hugo Hoppe was in business. He ran stage lines in the park and on the Cooke City road on the side. Joe Keeney was keeping one of the two or three saloons In the place and running a boarding house. The late Billy Hall was running a store there, as were the Hefferlin brothers. There were a few other business houses and a few private dwellings. It was a lively place. A man could get anything from a black eye to a horse race.

These were wild and wooly days, with little law and less order. Horse racing was the common Sunday amusement and sometimes the races resulted In a “drunk” being killed. But no one thought much about it. When an accident happened, the body was burled and the program went on. A man could get quick action on his money in Cinnabar, whether in a stud poker game, a foot race or a horse race, and the sky was the limit.

Affairs of Business . . .

A number of business operations were conducted in Cinnabar between from 1883 - 1903. Although the community got off to a slow start, businesses increased their presence as tourist crowds increased. Some of these businesses are listed below, in no particular order. Obviously not all operated at the same time, and several are the same but with different owners/managers:

Hugo J. Hoppe, among the earliest gold miners at Virginia City Mt., he came to Cinnabar in the mid 1880s and received title to 160 acres of land in the area. He formed the Cinnabar and Cooke Transportation Co. and by 1885 had reportedly established the somewhat crude log Cinnabar Hotel that came under the ownership of several individuals over the years including his son Walter, who had been managing the saloon associated with the hotel. A stable and blacksmith shop was also a part of the hotel operation.

Cinnabar Hotel

The history of the Cinnabar Hotel(s) is confusing at best, with a multitude of owners/proprietors over the years. Joe Keeney, one of the original land owners in the area, established a hotel with related stables, barns, etc., at least by 1885, also and guided early visitors through Yellowstone. He also maintained a saloon in connection with the hotel. The Livingston Enterprise noted in June 1886 that H.J. Hoppe had been leasing the hotel for the first six months of 1886, and that Keeney was regaining proprietorship at the end of Hoppe's lease.

A year later the paper again announced that Keeney was operating the hotel, when the Livingston Enterprise described him as, "the irrepressible proprietor of the Tourists’ Pleasure Resort.". He was again noted as running the hotel in 1887 in conjunction with a saloon and livery stable. In December 1888, the Enterprise disclosed that, "Joe Keeney, of Cinnabar, has sold his hotel and saloon business, at that place, to A T. French. The deal was conciliated in Livingston on Thursday, both parties being here." French later passed it on to M.T Williams in December 1889, who sold it to John F. Work in April 1890. In May 1891, Work "disposed of his interest in the Cinnabar hotel, furniture and fixtures. to William A. Hall for a consideration of $900. Mr. Hall, who has been manager of that hostelry during the past year, will make material improvements in the service to accommodate the increasing business." As noted in a photo below, the author believes Hall made substantial physical changes to the hotel/store, both interior and exterior. In June 1892, H.J Hoppe was listed as 'managing' the hotel. The article also mentioned that Joe Keeney was running a lodging house and eating house that was "liberally patronized." Confused yet??

It has been written that sometime after 1892, the Hoppe family gained control of the Cinnabar Hotel (which one?) and operated it through 1903. Some sources say it was run by the family after that point in time, perhaps to sagebrushers or other travelers not using the railroad.

Lee B. Hoppe, Hugo’s son, operated the Cinnabar Store, advertised in 1892 as the only store in town.

T.J. Loughlin & F.R. Brazil operated a restaurant and saloon in the mid-1880s.

W.A. Hall, Golden Rule Cash Store beginning in 1892 and operated camping outfit with teams, wagons & drivers. The W.A. Hall Co. housed a general store, a beer hall and a restaurant. Hall closed the store down and moved his stock to Gardiner in 1903 He also operated a store at Aldridge.

O.M. Hefferlin of Livingston operated the OK Store for time.

Larry Link, later of Gardiner fame, ran a saloon and pool hall with Alfred R. Christie. He reportedly also operated the Link & George saloon.

Smith & Holem Stage & Transportation, "a specialty of catering to the desires of tourists in furnishing local camps with hacks, carriages and saddle horses for their conveyances. Competent drivers and guides are provided, with headquarters at Cinnabar, Montana." 1903

M.A. Holem, "This general store has had a successful business career, first starting in August, 1897, with a small stock in a room at the corner of Main street and South avenue. By trying to please the public in honest prices and just deal ings, M. A. Holem was forced to establish herself in larger quarters, now occupying the post office building near the Park line depot.

Hobbs & Link, National Park Hack & Express Line, 1884

Earley & Holmes, Livery Feed and Sale Horses, ca1883-84

W.W. Wylie, who operated the Wylie Permanent Camping Co. into and around Yellowstone, maintained a barn and livery for his equipment to transport visitors on tours of the park.

Shaw & Powell arranged camping trips into the park from the Cinnabar Depot and no doubt had some transportation facilities in the area.

A.T. French operated the Cooke Transportation Line in the late 1880s.

A.W. Chadbourn provided passenger service to Yellowstone in 1884 and later operated a park camping company in conjunction with his business.

Wilbur Williams, Daily Stage & Express, Yellowstone, Gardiner, Cinnabar

Wakefield & Hoffman, Yellowstone Park stagecoach operations.

Wakefield & Ennis, operated camping tours into Yellowstone for at least 1896-1897.

M.T. Williams, ran the Cinnabar Hotel for a time.

During 1898 the Report of the Acting Superintendent of Yellowstone listed the following parties from Cinnabar licensed to guide camping parties into the park: AW Chadbourn, CC Chadbourn, EC Sandy, CT Smith, Frank Holem, Adam Gassert, WJ Kupper, Henry George, JW Taylor, HM Gore, RH Menefee and GW Reese.

1900 Census . . .

The Census of 1900 listed 94 persons living in Cinnabar. Occupations was were varied, but many falling into the category of Teamsters, Park Guides, and Day Laborers. There were, of course a smattering of bartenders/saloon keepers, store clerks, a couple of blacksmiths, a hotel keeper, carpenter, coal miner, and a barber. Many folks did not list an occupation.

Cinnabar Hotel ads from the Livingston Enterprise in Jan 1886, 1889, and 1891 respectively.

Left Top: Cinnabar Hotel (center left) and O.K. Store on right, ca1890. [Courtesy Autry Museum]

Left Bottom: Cinnabar Hotel, ca1890.

[Livingston Enterprise Souvenir, iJan1900]

Right: W.A. Hall General Merchandise store, ca1895. There is a restaurant in the building and the A-B-C Saloon. The Cinnabar Store is to the right. [Livingston Enterprise, 20Jun1933]

Below: Cinnabar townsite, ca1890. The taller building right center is the Cinnabar Hotel. The white building to its right may have become the O.K. Store a few years later. The image has been cropped for better visibility.

[Photo courtesy of the Doris Whithorn Collection, Yellowstone Gateway Museum]

Upon careful study of the windows and door of the store to the immediate left of the Hotel (above left), and the W.A. Hall store, the author believes that building later became the W.A. Hall General merchandise store (above right). It would have been added on to the left and upper floor and front remodeled.

In May of 1891, the Livingston Enterprise noted, "John F. Work has disposed of his interest in the Cinnabar hotel, furniture and fixtures. to William A. Hall for a consideration of $900. Mr. Hall, who has been manager of that hostelry during the past year, will make material improvements in the service to accommodate the increasing business.

Left Top: Lawrence Link Saloon and Pool Hall

[Livingston Enterprise, 4Jun1892]

Left Bottom: Loughlin & Brazil Saloon and Restaurant

[Livingston Enterprise Souvenir, 25Apr1885]

Top Left: Earley & Holmes Livery & Stables

[Livingston Daily Enterprise, 24Apr1883]

Top Right: Frank Holem, Blacksmithing & Horseshoeing.

[Livingston Enterprise, 26Mar1903]

The Coal Mines . . .

Horr (named Electric after 1904) was the site of the coke ovens of the Park Coke and Coal Company. The name was bestowed upon it in honor of either Harry Horr, the discoverer of the coal mines in the vicinity, or Major Jos. L. Horr, who in 1884 opened up, the coal mines. On Oct 22, 1887, The Livingston Enterprise announced the shipment of the first three carloads of coal on the Park train to Livingston and Butte. The village itself came into existence in 1888 as a result of the commencement of operations there by the Park Coal & Coke Co. The coal was mined nearby in a community that acquired the name of Aldridge in 1896. On July 1, 1888 the Horr post office opened with Laura A. Pinkston as postmistress. During the nineties the Montana Coal & Coke company became the owners of the property and by the year 1900 quite rapid advancement was made in the little village owing to the increased activities of the company. [An Illustrated history of the Yellowstone Valley, Western Historical Publishing Co., Spokane WA, 1907]

Cinnabar was also an important rail station for the gold mines of Bear Gulch/Jardine and Cooke City areas. Mining supplies were carried to Cinnabar from all over the country and delivered by various freight carriers in Cinnabar for transport to these areas. Gold, silver, and other ores and bullion were likewise transported by rail from Cinnabar, as was travertine from the quarries above Gardiner.

Left: Post card view of Electric, formerly Horr, with the coke oven in front. The Yellowstone River is in the far background. Cinnabar was a few miles up the valley to the right. Closing of the mines at Aldridge spelled doom for the town of Electric and by 1915 the post office closed.

Right: Post card view of the town of Aldridge, located up in the mountains and situated along a lake. The town of Lake was in existence by 1894. It had also been called Little Horr and The Camp at the Lake, and was later renamed Aldridge. Labor problems closed down the mines in 1910, with the post office closing by the end of the year.

The Final Days . . . .

In 1902 the land dispute with Jim Cutler was finally settled and the rail line continued on to Gardiner as originally planned. This move rang the death knell of the town of Cinnabar, and the small community quickly faded away after that time and the once bustling town turned into a ghost town. Cinnabar was removed as a station stop on May 3, 1903, and the post office was closed shortly after on June 15. An effort was made by the railroad to change the name of Gardiner to Cinnabar, to maintain the existing 20-year legacy of that station name, but the proud residents of Gardiner soundly defeated that effort. Many of the Cinnabar buildings were moved into Gardiner, while others were transported to Horr. The rail depot was loaded onto a flatcar and hauled into Gardiner where it was used as the freight depot. The only remaining evidences of the site today are some depressions in the ground, a few foundation stones, and broken pieces of glass and ceramics scattered over the flats.

Billings Gazette, 10Apr1903

Butte Miner, 30May1903

1920 View of Gardiner. The Cinnabar Depor can be seen at left within the circle.

Cinnabar - The Western White House . . .

In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt engaged on a grand western tour, taking him to Chicago, north through Wisconsin, Minnesota and North Dakota. Roosevelt and his companion, famed naturalist writer John Burroughs, arrived at Gardiner, Montana by train on April 8, 1903. The two men were greeted by their host, acting-superintendent Major John Pitcher. According to the Livingston Enterprise on Aug. 7,

“President Theodore Roosevelt will arrive in Livingston tomorrow morning at 9 o'clock from Billings. He will leave Billings at 5:40 o'clock. The president and his party will remain in Livingston only fifteen minutes and will then proceed to Cinnabar, at which place he will arrive at 12:30 o’clock and vyill be met by Troop C of the Third cavalry, Major Pitcher commanding. All of the party traveling with the president, with the exception of John Burroughs and Dr. P. M. Rixey, surgeon general of the navy, will remain in the private train at Cinnabar.”

While the President was making merry on his wanderings in Wonderland, the remainder of the party left stranded in Cinnabar seemed to not be particularly thrilled with their plight and the area. The Butte Daily Post commented on the 10th that,

“Cinnabar, near the entrance to the Yellowstone National park, the present seat of the executive offices of the nation, isn't an attractive place. It has no public parks, no theaters, no extensive society, no charming homes, no palatial hotel. In fact, there isn’t much at Cinnabar except a depot, a few houses, a store, a livery stable, two saloons and, at present, a bunch of exceedingly bored gentlemen from Washington. The president's special train stands on a siding near the depot, and in it the aforesaid bunch lives and eats and drinks and smokes and wonders what on earth to do. All hands sit around all day and deplore in fervid language the fate which keeps them tied up at a place like Cinnabar. They look down on the river towards Horr and the Devil's Slide meets their eyes—but the devil refuses to slide for their edification. They look up the river and they see only bare hills, with some snowpeaks rising in the distance, but there no longer is anything interesting in the view. Now and again some miners come over from Horr and whoop things up a little at one of the two saloons, but they refuse to go to the length of fighting or doing anything actually exciting.”

Roosevelt and his party, guided by Thomas Elwood Hofer, headed out the next morning for a tour of Yellowstone. On April 16, after a return to Fort Yellowstone, the presidential party again packed up the camp and traveled to the geyser basins in a horse-drawn sleigh, accompanied by Park concessionaire Harry Childs. The sleds eventually reached Norris Geyser Basin, where the party spent the night at the Norris Hotel. Proceeding the next day to the Fountain Hotel, they continued on to the Upper Geyser Basin where he watched the eruption of Old Faithful geyser. After viewing the famous geysers in the Upper Geyser Basin, Roosevelt returned to the Norris Hotel for another night’s stay, working their way from Norris to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

The President's Western Trip

Harper's Weekly, 4Jul1903

Click to enlarge.

President Roosevelt's Special Train at Cinnabar, Montana

Underwood & Underwood Stereoview

Click to enlarge.

As the trip ended, Roosevelt returned to Mammoth Hot Springs, where he agreed to speak at the Masonic cornerstone-laying ceremony on the 24th for the future archway located at the northern entrance to Yellowstone, which would later bear his name. In his speech dedicating the arch, Roosevelt praised Yellowstone. “The geysers, the extraordinary hot springs, the lakes, the mountains, the canyons, and cataracts unite to make this region something not wholly to be paralleled elsewhere on the globe,” Roosevelt proclaimed. “It must be kept for the benefit and enjoyment of all of us.” Boarding his train after the ceremony, he headed north to Livingston and east toward Washington D.C., making a multitude of 'whistle-stops' along the route.bound east for Omaha. It had been a proud and exciting few weeks for the folks of Gardiner and Cinnabar

Post Script:

The Cinnabar & Clark Fork Railroad

Late in 1883 efforts were made by the mining interests in Cooke City and the NPRR to extend the Park Branch line beyond Gardiner to the mines in Cooke City. This feat would have required passing through the northern border areas within Yellowstone Park. It became a volatile issue and stirred 10 years of debate in Congress. Cooke City, the greatest mining district of Montana, as described by the Livingston Enterprise, reported on Jan 5, 1884, “... It is believed that Congress will grant the right of way through the park with little opposition, as the road will run along the ... border of the park and interfere with no point of interest. This would be a great boon to Cooke City and would increase the value of her mineral discoveries to an incalculable extent. ... Cinnabar would also have a great accession of prosperity ... even without the ore reduction works the township proprietors propose to erect.”

Two weeks later the Enterprise noted incorporation of the line, “The company is to build and operate a railroad from Cinnabar to Cooke City ... and it also has for an incidental object the erection of ore reduction works at Livingston. The names of the incorporators as they appear in the certificate are Col. Geo. O. Eaton and Geo. A. Huston, of Cooke City, D.E. Fogarty and Major F.D. Pease, of Livingston, and George Haldorn, of Billings, and beside those a glittering array of Eastern capitalists, some of them of national fame, are connected with the company.”

The Bozeman Daily Chronicle reported on the situation on 23Jan1884, “It was known as the “Bullion Railroad Company” with Capital Stock of $1,000,000 and Articles of Incorporation were filed in Jan 1884 at Helena. By February 1885 a bill was working its way through Congress that is to segregate the northern tier of Yellowstone Park into private lands so that the railroad from Cinnabar to Cooke City could build along that section of land. Many miners, speculators and profiteers in Gardiner were awaiting news that the bill passed so that they could file claims on the most valuable pieces of property for themselves; either as homesteads, mining claims or for speculative purposes to resell to the railroad or other potential businesses. Although the bill had merely passed the House and had not yet been considered by the Senate, through some communication error, word was put out that the bill had passed and rapidly spread through the local community. Dozens rushed out to file location notices, including, George Huston, Joe Keeney, A.L. Love, C.T. Hobart, Hugo Hoppe, Park Supt. R.E. Carpenter and assistant park superintendent S.M. Fitzgerald. Needless to say, none of the property claims were valid as the bill never did pass the hallowed halls of Congress.”

Various controversial efforts to build the railroad that were hotly debated continued until 1892. Finally, Thomas F. Oakes, president of the NPRR, finally declared at the end of that year, “his company had thoroughly examined the mines at Cooke City and the various routes to them, and that under no circumstances would his company build a road to them.” Case closed – much to the relief of Yellowstone enthusiasts.